Architecture of Continuity: Extending Life, and Community Through Adaptive Renewal

12.06.25

Case study

Retrofitting is the process of adding, altering or upgrading elements in existing buildings – particularly older or historic ones – where spatial needs, environmental performance, or functionality no longer align with current demands.

As a more sustainable alternative to demolition and rebuild, retrofit allows us to reduce emissions while extending the life of buildings already embedded in our towns and cities.

In the UK, the built environment is responsible for 25% of our total climate emissions, with the construction industry contributing nearly 40% of our carbon output. This includes embodied carbon from the manufacturing of new buildings, as well as operational carbon from the running and maintenance of those already in use.

With a national target of net zero emissions by 2050, retrofitting our existing buildings will be critical in reducing our overall footprint. 80% of the buildings we will occupy by 2050 already exist – giving us a chance to work with what’s already here, before building something new.

Yeatman Court

From Factory to Home

HKR Architects’ retrofit of a historic 1918 art deco building in North Watford – originally Yeatman’s Sweet Factory and later the headquarters of Mothercare – puts this approach into practice.

The building’s character has been carefully preserved while integrating modern, sustainable design elements. The existing structure was adapted to provide 145 affordable homes. A new two-storey rooftop extension was also introduced using lightweight construction methods, slotting into place.

The original structural frame was largely retained and sensitively modified to suit contemporary residential standards, while the façade was upgraded with energy-efficient enhancements.

By balancing conservation with adaptation, the project offers a clear example of how existing buildings can be thoughtfully reimagined balance heritage value with housing needs.

The T-shaped building sits on a site in North Watford, roughly 1.3 hectares in size, bounded by Cherry Tree Road, Berry Avenue, and Foxhill. Located close to the town centre, the area benefits from strong transport links, with London Euston just over 20 minutes away by rail. The surrounding area is characterised by quiet, leafy streets lined with terraces and semi-detached houses.

The original complex stood out. Constructed in 1918 as a factory, the site was later adapted and expanded to form a commercial headquarters.

It sat apart from its domestic surrounding – a steel-clad, 3-storey warehouse to the south and a white, flat-roofed office block to the north, rising to 5 storeys. The office wings were structurally distinct, with a rooftop extension added to the east wing in the 1980s.

The scale, materials and massing stood in contrast to the pitched roofs, red brick and private gardens of the surrounding homes. Over time, however, it became a familiar feature of the local streetscape.

Following its sale in 2019, the office building retained lawful use for commercial, storage, and distribution, though it held no formal designation in the Watford District Plan. It was, however, promoted for residential development in the emerging Local Plan.

While there were no listed structures or conservation area constraints, the site’s scale and position within an already settled neighbourhood invited close attention.

Its layered planning route – through permitted development, detailed applications and phased approvals – speaks to the challenge of adding homes while respecting the existing fabric.

Preparing the ground

A layered project calls for a layered process. With Yeatman House, change arrived gradually, through a sequence of coordinated steps. It began with a permitted development (PD) submission for change of use, an early milestone that unlocked the potential of the existing structure.

This was followed by a full planning application to rework the façade, aligning it with its new residential role while preserving its original character.

The transformation also involved targeted demolition. On the ground floor, removing a connecting section between the main block and warehouse created a clearer divide, allowing the T-shaped volume to be treated as a standalone structure for retrofit.

A second cut at the former entrance opened the opportunity for a new ground floor frontage, reorienting the building’s relationship with the street. At roof level, a previous 4th floor extension was carefully adapted to accommodate a full two- storey addition.

Each intervention prepared the building for its next chapter -preserving what mattered, removing what no longer served, and creating space for what could come next.

Adapted for living

With the structure prepared and permissions in place, the design approach turned to making the existing building liveable. The retained frame of the T-shaped block formed the basis of the new layouts, with deep floorplates reconfigured to meet contemporary residential standards.

This included ensuring all habitable rooms received adequate daylight, in line with updated PD regulations. New cores were introduced to rationalise circulation, and floorplans refined to improve access to natural light and air.

Above, the two-storey extension added 44 new homes, bringing the total across the scheme to 145. Its massing was set back to reduce the visual impact on neighbouring properties and to create private amenity terraces for the upper-level apartments.

Resonance

The final piece of the puzzle was a carefully considered façade that preserved the building’s identity while adapting it for residential use.

The original façade’s horizontal emphasis, with metal-framed, multi-pane windows and dark blue spandrels, was retained in the new design to maintain its character while incorporating modern improvements.

Single-glazed windows were replaced with double-glazed units to improve thermal performance. Additional light blue spandrel panels were introduced to conceal internal partitions, preserving visual continuity while mitigating solar heat gain from the high percentage of glazing.

This thoughtful integration allowed the spandrels to serve both aesthetic and functional roles, retaining the building’s original character while improving its energy efficiency.

A white render finish was applied across the external walls to unify the old and new elements. The detailing of the parapets, cornices, and window transoms was aligned with the original design, ensuring seamless integration with the new extension and meeting current energy performance standards.

Yeatman Court demonstrates how adaptive reuse can transform a historic building into a modern, sustainable, and liveable space.

Antony & Roderick House

In support of continuity

A testament to urban renewal tucked between Southwark Park and the elevated rail lines of southeast London.

Antony & Roderick House is stiched within an evolving urban fabric, where residential developments, industrial remnants, and regeneration schemes intersect.

The site was identified by the housing association and local authority as a chance to deliver new mixed-tenure homes, while retaining existing buildings and enhancing the wider estate.

HKR saw an opportunity for quiet transformation – one that could extend the life and capacity of the buildings without displacing the community inside.

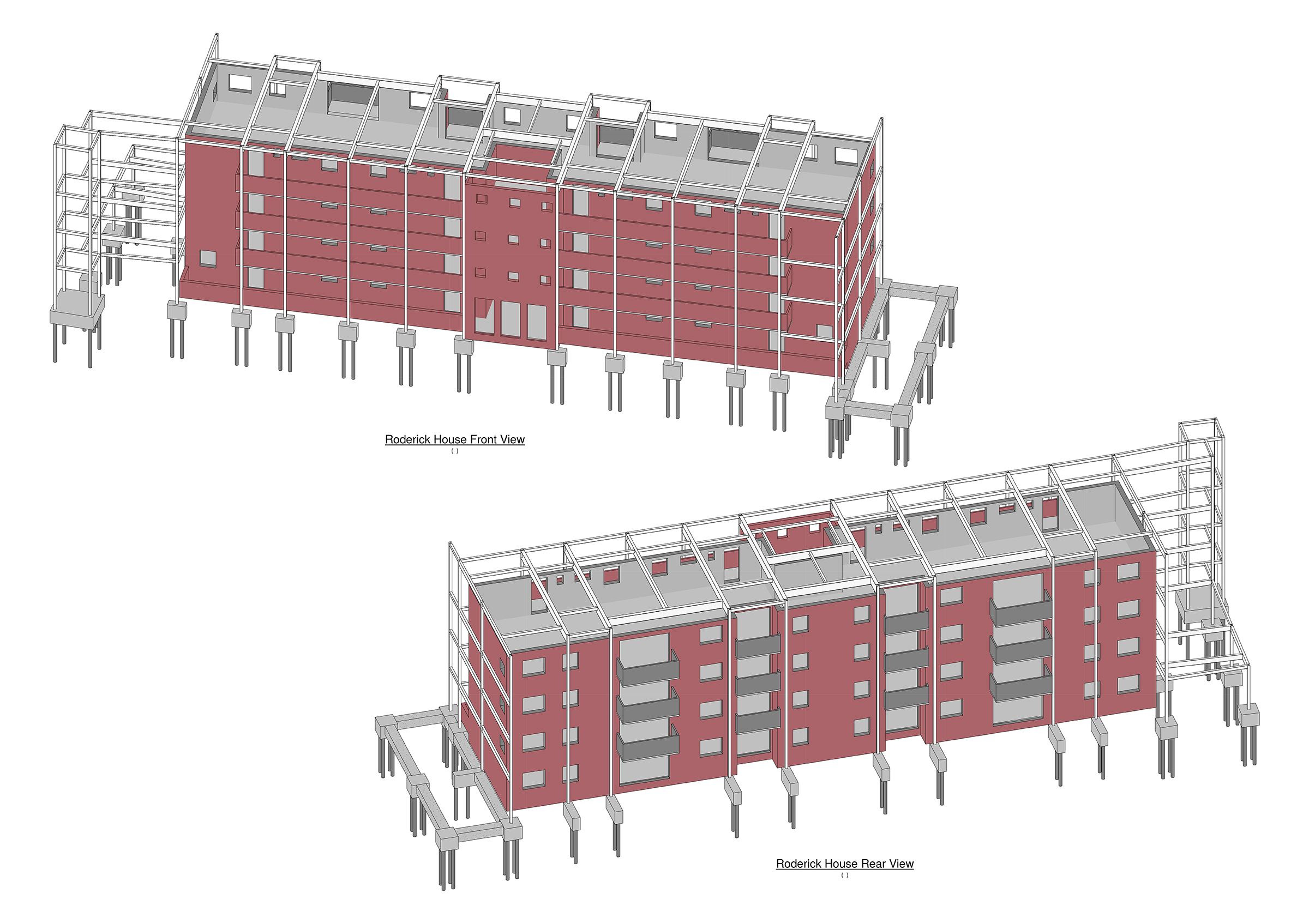

Originally four storeys with 16 flats each, the buildings were expanded by two modular storeys to deliver 30 additional homes.

The existing fabric was retained and upgraded with new fixed cores, an improved roof, and softer landscaping – boosting energy performance and raising the standard of everyday life.

Our expertise in modular construction, ideal for compact, occupied sites like this, offered a streamlined alternative to traditional methods, reducing noise, dust, and disruption.

It enabled a precise, low impact build that allowed the estate to grow while life continued undisturbed below.

Antony House and Roderick House sat on a compact site in Bermondsey, in northeast Southwark, a London borough. Positioned between Abbeyfield and Aspinden Roads, they lie just behind the railway line near Southwark Park.

Built in 1953 and owned by Lambeth & Southwark Housing Association, the original mid-rise, red brick blocks feature white-framed windows, concrete rear balconies, and open walkways facing a shared forecourt.

They have a total of 32 socially rented and fully tenanted flats, with no private leaseholders.

The surrounding area reflects a layered cityscape – low-rise terraces, dense estates, and prominent buildings like Maydew House, co-exist with light industrial units nestled beneath the nearby viaduct.

Strong public transport links – including multiple rail and bus routes – connect the site to central London, highlighting its potential for modest, well-integrated intensification.

While the forecourt and garden spaces offered scope for communal use, they remained largely underused.

Its gaps and edges – unused sheds, overgrown corners, awkward circulation – helped shape the brief: to improve legibility, reimagine shared space and create a stronger sense of place.

At ground level, the bin stores sat beside the main entrances, spilling into view and cluttering the threshold. Above, the circulation core was marked by a narrow band of windows – opaque and hesitant.

HKR responded to what was absent. We saw the potential to reframe and define the entrance and make access both legible and inviting.

A Bridge Between Homes

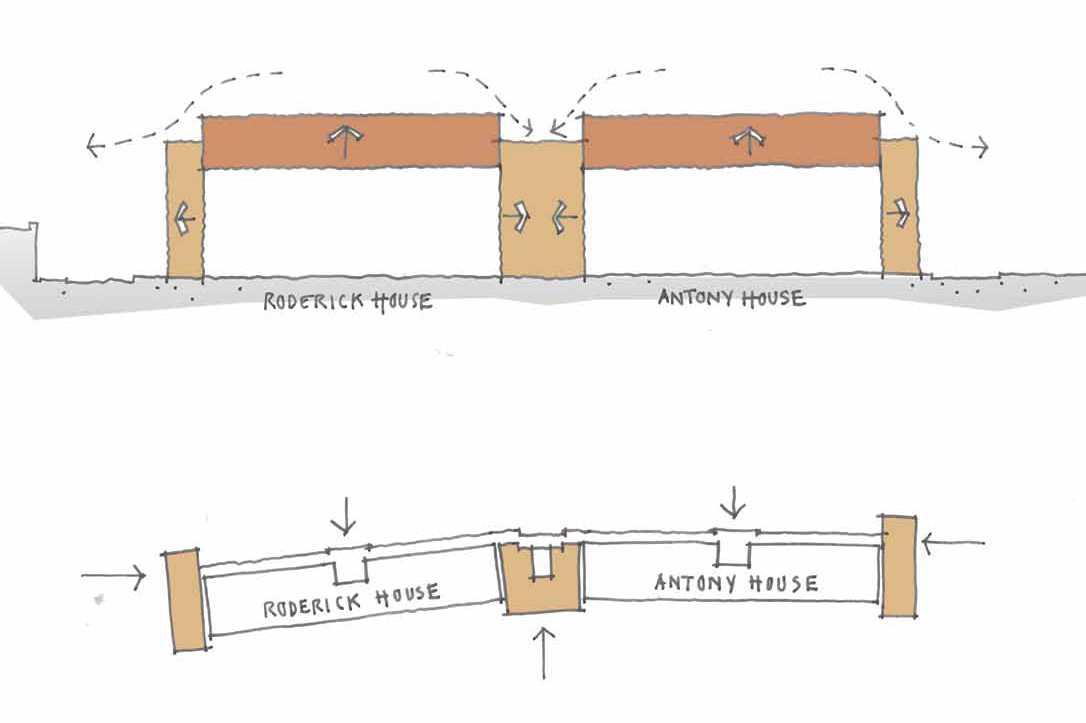

Our concept is rooted in care, not only for the architecture that came before, but for the community still living within. The additions feel like natural extensions rather than impositions: two new “bookends” that anchor the blocks, a central infill that ties them together, and a pair of rooftop forms that rest lightly above. Together they frame the original buildings with subtle intent.

These interventions extend the structures upward and outward, making room for new homes while improving circulation, entrances, and shared spaces. The result is a graceful, cohesive project that respects the existing fabric while reading as a confident, contemporary evolution.

The new bookends rise to 5 storeys, each containing duplex maisonettes with living spaces at street level and bedrooms above, bringing activity back to the ground floor and softening the transition from public to private.

Between them, the 6-storey infill introduces 30 additional homes above shared ground-floor uses and a new communal lift, transforming a previously underused gap into the spatial heart of the estate. Day-to-day movement is enhanced without unsettling the original rhythm.

Lightweight rooftop extensions replace the ageing, pitched roof structure, adding two storeys and finished in tones that complement the original brickwork. Across the estate, several upgrades lift the everyday experience for residents.

Bin and bike stores are reconfigured to feel safer and easier to navigate, while tired pram sheds make way for secure, purpose-built storage. At ground level, the forecourt is re-landscaped with clearer routes, new planting and softer lighting, turning overlooked edges into welcoming, usable spaces.

Day-to-day movement is enhanced without unsettling the original rhythm

A Balancing Act

The new volumes – two bookends, a central seam, and a rooftop extension — extend the estate with intention, not excess. Every addition was shaped by restraint.

Scale and structure were calibrated to the proportions of the original blocks and the pattern of the streetscape. By setting back the upper levels, the design protects views, welcomes daylight, and keeps the ground floor amenity clear, generous, and intact.

On a dense, inhabited site, modular construction was a deliberate choice – not just for efficiency, but for precision. HKR’s seasoned experience with MMC guided an approach that balanced accuracy with build quality, keeping the programme tight and the process dependable.

Built off-site and delivered to tight tolerances, the new elements aligned seamlessly with the existing fabric. The predictability of modular construction ensured consistent progress, protection from weather delays, and improved safety by reducing site activity. This also softened the build’s impact on residents by limiting noise, dust, and site traffic.

Above, a finely engineered steel transfer structure spans the original building, forming a stable base for the new rooftop homes. Designed to work within the constraints of the existing frame, it delivers strength without unnecessary weight – a targeted intervention that preserves the structural integrity below while enabling vertical expansion.

The modular approach also supported design flexibility, allowing considered forms and subtle details to be delivered though a repeatable system.

Fewer deliveries, reduced site activity, and more efficient material use also helped lower the project’s environmental footprint. MMC techniques offer proven reductions in construction waste – in some cases to under 1%.

Complimentary

The façade strategy builds on the language of the original 1950s blocks, drawing from a refined material palette to anchor the extensions in place.

For the lower half, variegated multi-stock brick was selected for its tonal closeness to the existing masonry, its subtle shifts in colour and texture bringing depth without distraction.

Projecting soldier courses – contrasting sections of vertical brickwork – detail the bookend windows.

For the upper extension, soft red-brown zinc cladding caps the rooftop homes, echoing the linear character of the brickwork blow.

Dark grey aluminium windows and glazed door panels confidently tie the new and existing elements together. The result has a visual balance and easy street presence – a study in tone, texture, and proportion.

By blending preservation with innovation, the retrofit enhances both the building’s identity and its performance, offering a model for creating much-needed housing in future urban regeneration.